In Investing is a "Loser's Game", we learned that investing success starts with not making big mistakes. Don’t self-sabotage. This is critical for maximizing your chance of achieving your financial goals.

We have also established that goals are personal. Still, it is common for people to dwell on whether they are “beating the market”. Getting caught up in this competitive view draws you into the “loser’s game”. It lures you into risks that are incongruent with the goals you have thoughtfully pre-committed to.

It’s not only the case that you shouldn’t be distracted by trying to “outperform” — you [almost certainly] cannot. The reason flows from a simple idea.

Outperformance needs a counterparty

The Nature Of Relative Performance

Market’s are not zero-sum. Broad benchmarks track the performance of the overall market. If the economy grows, a business's earnings can expand without needing to steal market share from competitors.

Relative performance is zero-sum. Benchmarks represent the whole. If you outperform someone else must underperform.

The world’s wealth measures in the hundreds of trillions of dollars. Professional investors claw for outperformance to justify earning a fee on a tiny sliver of those investable assets. If you were stepping onto a basketball court against Michael Jordan you would have no delusions about your odds of success. The abstract nature of competing for investment “alpha” (an industry term for excess returns) belies how outmatched you are as a retail investor.

To make matters worse, the investment industry loves the “democratization” narrative that suggests that having more information at your fingertips increases your chance of “beating the pros”. Casinos know books that promise to help you beat the dealer will create more customers than sharps.

What Does It Take?

To “beat the markets” you must:

- have an edge

- be able to be contrarian

Having An Edge

Since the evolution of markets selects for the fittest competitors, Michael Mauboussin prompts you to ask, “Who is on the other side?”

He makes the case that outperformance is compensation for ironing out or arbitraging the inefficiencies in markets. Professor Lasse Pedersen describes markets as “efficiently inefficient” which is another way of saying that unless you are one of the elite competitors in the outperformance Olympics, you should not enter. Just because you cannot see your opponents’ bulging muscles or graceful moves doesn’t mean you are in the same league.

What You’re Up Against

In Laws of Trading, author and trader Agustin Lebron paints a picture of your opponent

The Competitiveness of Financial Markets

It is difficult to describe to the novice trader, or even y experienced retail trader, exactly how competitive modern financial markets are. Investment banks, hedge funds, and proprietary all mobilize massive resources to develop tiny edges. It begins w hiring. The best of these firms spend many tens of thousands of dollars per hire in an attempt to woo the very best minds universities produce.

These new hires are taught by some of the best traders and researchers in the business through a challenging and continuous training program. I've seen these programs first-hand. The main is taught and absorbed at a significantly higher speed than the classes at even the best universities. And it takes these excellent res hires somewhere between 6 and 18 months to become a net positive to the trading desk to which they're attached.

Traders stare at markets all day every day and are extremely well-incentivized to find edges, to find trades. Firms also employ the best programmers and technologists and have some of the highest per-employee IT spending of any business. Not surprisingly, the research infrastructure available to study ideas integrates petabyte-scale databases with advanced analytics and custom tools.

The reason for this breathtaking deployment of resources is the extreme competitiveness of the market. In point of fact, there are no natural barriers to entry Anyone can compete, if they have a good idea, and by modern venture capital standards they can do so with modest capital requirements. As a result, the edges of real-life trades are small.

It's easy to convince yourself unless you've seen it firsthand that your opposition isn't really that skilled, that motivated, that well-funded. Call it a specific form of overconfidence bias. But in my career, I've met some incredibly sharp and motivated traders, and I'm sure there are hundreds more I haven't met. These are the people with whom you're competing. In modern markets, the vast majority of the orders and trades that happen are between professionals. So the marginal trader in modern markets is incredibly skilled, motivated, and well-funded. Does the edge you've discovered, the story you're telling yourself, make sense in this context? Is it really possible that your competition, this competition, may have just flat out missed it?

A.I. researcher Eliezer Yudkowsky forcefully agrees in chapter 1 of Inadequate Equilibria

If I had to name the single epistemic feat at which modern human civilization is most adequate, the peak of all human power of estimation, I would unhesitatingly reply, “Short-term relative pricing of liquid financial assets, like the price of S&P 500 stocks relative to other S&P 500 stocks over the next three months.” This is something into which human civilization puts an actual effort.

- Millions of dollars are offered to smart, conscientious people with physics PhDs to induce them to enter the field.

- These people are then offered huge additional payouts conditional on actual performance—especially outperformance relative to a baseline.

- Large corporations form to specialize in narrow aspects of price-tuning.

- They have enormous computing clusters, vast historical datasets, and competent machine learning professionals.

- They receive repeated news of success or failure in a fast feedback loop.

- The knowledge aggregation mechanism—namely, prices that equilibrate supply and demand for the financial asset—has proven to work beautifully, and acts to sum up the wisdom of all those highly motivated actors.

- An actor that spots a 1% systematic error in the aggregate estimate is rewarded with a billion dollars—in a process that also corrects the estimate.

- Barriers to entry are not zero (you can’t get the loans to make a billion-dollar corrective trade), but there are thousands of diverse intelligent actors who are all individually allowed to spot errors, correct them, and be rewarded, with no central veto.

This is certainly not perfect, but it is literally as good as it gets on modern-day Earth.

I don’t think I can beat the estimates produced by that process. I have no significant help to contribute to it. With study and effort, I might become a decent hedge fundie and make a standard return. Theoretically, a liquid market should be just exploitable enough to pay competent professionals the same hourly rate as their next-best opportunity. I could potentially become one of those professionals, and earn standard hedge-fundie returns, but that’s not the same as significantly improving on the market’s efficiency. I’m not sure I expect a huge humanly accessible opportunity of that kind to exist, not in the thickly traded centers of the market. Somebody really would have taken it already! Our civilization cares about whether Microsoft stock will be priced at $37.70 or $37.75 tomorrow afternoon.

I can’t predict a 5% move in Microsoft stock in the next two months, and neither can you. If your uncle tells an anecdote about how he tripled his investment in NetBet.com last year and he attributes this to his skill rather than luck, we know immediately and out of hand that he is wrong. Warren Buffett at the peak of his form couldn’t reliably triple his money every year. If there is a strategy so simple that your uncle can understand it, which has apparently made him money—then we guess that there were just hidden risks built into the strategy, and that in another year or with less favorable events he would have lost half as much as he gained. Any other possibility would be the equivalent of a $20 bill staying on the floor of Grand Central Station for ten years while a horde of physics PhDs searched for it using naked eyes, microscopes, and machine learning.

In the thickly traded parts of the stock market, where the collective power of human civilization is truly at its strongest, I doff my hat, I put aside my pride and kneel in true humility to accept the market’s beliefs as though they were my own, knowing that any impulse I feel to second-guess and every independent thought I have to argue otherwise is nothing but my own folly. If my perceptions suggest an exploitable opportunity, then my perceptions are far more likely mistaken than the markets. That is what it feels like to look upon a civilization doing something adequately.

In other words, to compete for outperformance you need a unique, clearly defined edge. Agustin Lebron describes edge as the reason an idea makes money:

There are many ways of losing money in trading and precious few ways of making it. Such rare beasts demand reasons for believing they exist. The fundamental axiom of edge is this: all trades that have an edge are profitable because there is some fact about the world that you understand and can act on that the marginal participant doesn’t understand or can’t act on. Thus describing your edge is explaining what you know and can do which others do not and cannot.

The seemingly discouraging reality (you will learn later why you should not be discouraged if you focus on the right things) is the scarcity of “alpha”. There are limited opportunities to press an edge. Before you can even attempt to exploit an accessible edge, you must identify it. This requires contrarian thinking.

The Ability To Be Contrarian

Charlie Munger on the necessity of being contrarian:

Mimicking the herd invites regression to the mean. Here’s a simple axiom to live by: If you do what everyone else does, you’re going to get the same results that everyone else gets. This means that, taking out luck (good or bad), if you act average, you’re going to be average. If you want to move away from average, you must diverge. You must be different. And if you want to outperform others, you must be different and correct. How could it be otherwise?

Not only is contrarianism necessary, it’s difficult. There are 2 sources of difficulty:

- Intellectual/analytical Consensus is usually correct. The wisdom of crowds is formidable. Not only do you need to be right, you need to understand why others are wrong. This requires strong analytical frameworks to appreciate the multi-level thinking in the poker game of outperformance.

- The “Keynesian beauty contest”: You, as a judge, are trying to guess which face the other judges prefer instead of the one you find most attractive.

- The 2/3 Game: Imagine a room of participants each submitting an integer between 1 and 100. The winner is the guess that is 2/3 of the mean of all submitted numbers.

Metaphors for the multi-order thinking required in markets

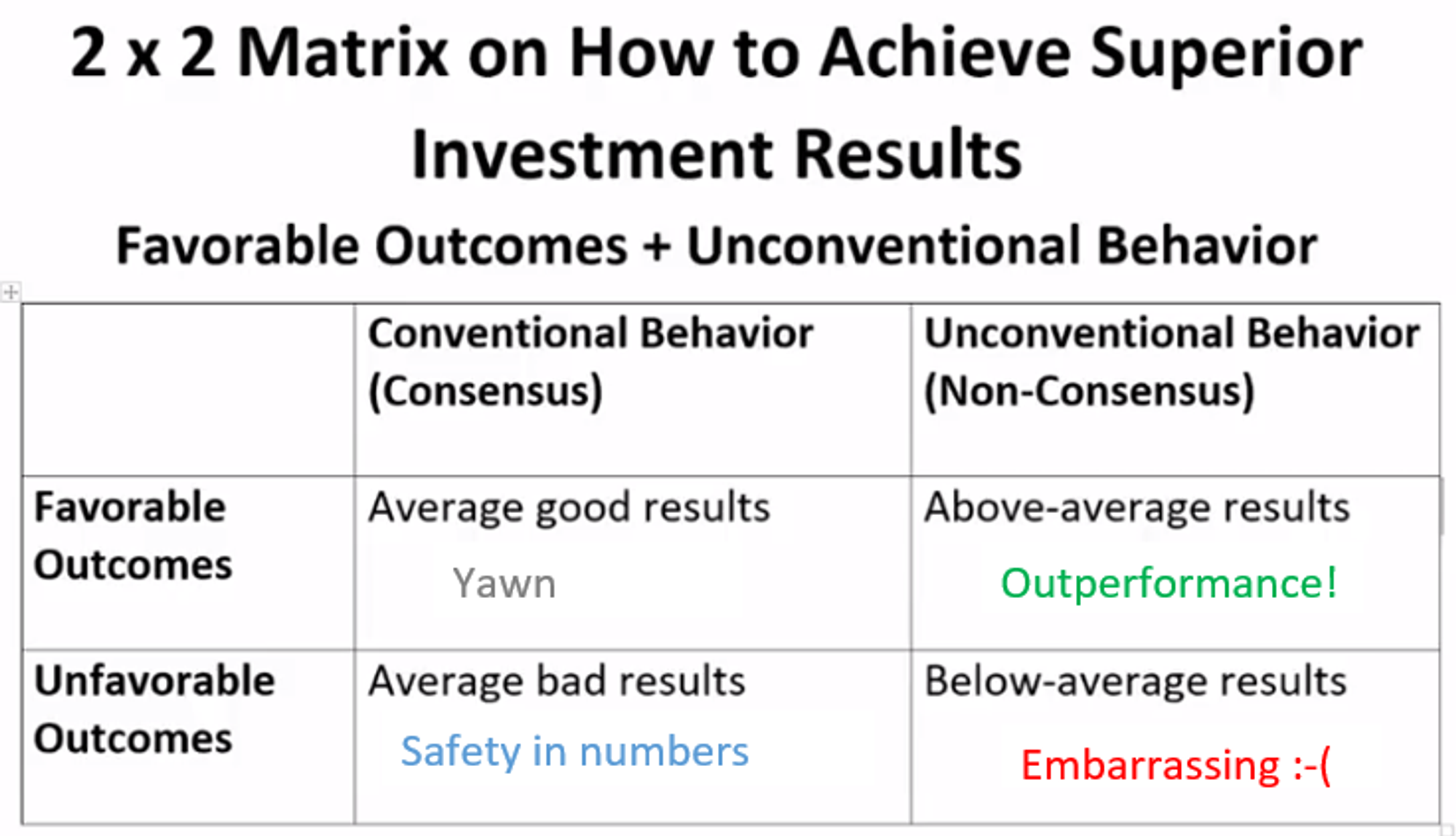

- Social Incentives Howard Mark’s visual summarizes the challenge:

The top right quadrant of this editorialized matrix is the only box that corresponds to outperformance. The bottom left box is a lesson in incentives skewered by the folk expression “You never get fired buying IBM”. The challenge with being contrarian is not just the need to be right when everyone is wrong but the unbalanced risk of embarrassment. This is especially relevant for people who manage client money. If their fees are based on assets, it is risky to stray from benchmarks.

Outsourcing The Quest For “Alpha”

If you are convinced that you aren’t going to find outperformance in between cooking dinner and taking your kids to soccer, you might be tempted to hand your savings over to one of these brilliant pros.

Temper your expectations. There are 2 related problems.

Adverse Selection

If you are familiar with the lemon problem from economics, the following findings will not surprise you:

- Hedge Fund Managers With ‘Skin in the Game’ Outperform — But They’re Also Less Likely to Take Your Money. Hedge fund managers tend to keep funds small when their own capital is at stake, achieving “superior returns” by locking out outside investors. (Institutional Investor)

- One study of “skin in the game” shows that while it aligns incentives, it has the effect of crowding out third-party investors from the best strategies. Greater inside investment incentivizes managers to better manage the size-performance tradeoff discussed above. But it does so by restricting the entry of new outsider capital to the funds in which managers are invested. Insiders own $400 billion of the $3 trillion invested in hedge funds globally. (Zuckerman’s Curse and the Economics of Fund Management)

- In an interview with StrictlyVC, venture capitalist Mitchell Green lists the 10 criteria his firm uses to prospect investments. He knows they will never find one that checks every box.

If you call 1000 companies, you might find 10 that meet all the criteria. None of them will take your money. They won't take my money. They won't take Sequoia's money, they won’t take GA’s money, nobody's money. And so you're trying to find ones that meet five to seven that are awesome.

I refuse to join any club that would have me as a member. - Groucho Marx

Scale

There is a trade-off between a strategy’s alpha and scale. This is intuitive. If Warren Buffet found an edge in the ice cream parlor business it wouldn’t move the needle as he needs to produce returns on billions of dollars. The most profitable sources of alpha exist in niches, often for structural reasons and are highly capacity-constrained.

Agustin Lebron’s description of niches

The Nature of Real-World Edges

The preceding discussion may make it seem that the nature of real-world edges is complicated and that to explain them requires a deep understanding of markets, huge datasets, knowledge of advanced mathematics, and subtle reasoning. Proving that a given edge is indeed present, and being able to run a trade based on it, may well require all of those things. But explaining an edge does not. In fact, the competitiveness of markets makes the very opposite true. Bearing these considerations in mind, recall this chapter's rule: If you can't explain your edge in five minutes, you don't have a very good one.

How can this be true? By way of explanation, let's describe some real honest-to-goodness edges that consistently make millions of dollars a year for the people who trade based on them:

- People who want to trade stocks need a middleman to make the process efficient and convenient. These middlemen, whom we met in Chapter 2, are known as market makers. Customers demand liquidity from market makers, the latter provide it, and in aggregate they make a profit for having done so.

- ETFs and other funds need to rebalance their portfolios periodically based on changes in the composition of the index they track. When these funds trade, people who provide liquidity should profit from doing so.

- Relationships between related securities should, over the long term, follow certain reasonable statistical properties. Identifying when these relationships are far from their historical averages can lead to trades that bet on the deviations disappearing over time. For example, the relationship between the on-the-run and off-the-run treasury bonds.

Each of these trades is an easily explained profitable trade. I just explained them. The story of their edge is straightforward and understandable to anyone with a reasonable knowledge of financial markets. Of course, transforming this straightforward story of edge into a trading strategy that actually is profitable is no mean feat. Each of these trades is well known, well understood, and attracts plenty of competition. You have to be very good to win at this level.

You might object that these particular trades are easily explained, but perhaps some other more complex ones aren't. This could be true, but those edges are likely to be less profitable. The discussions in the preceding chapters about the competitiveness of financial markets give a clue about why this is the case.

The more complex the story of edge becomes and the more pieces there are to the trade, the higher the number of things that have to be true, to go right, and to remain true, in order for a trade based on this edge to be profitable. Moreover, as you know, markets adapt over time. A very complex edge with lots of moving parts is unlikely to be one that (a) is broadly applicable to many situations, and (b) remains profitable over the long term. Simple stories are robust and, even if they are competitive, they are reliable

To make matters worse, as a strategy succeeds everyone notices. The talented professionals who understand the strategy are poached or bid up reducing the margins of strategy by raising its costs. Competitors copy the strategy further squeezing its margins. Faced with little hope of outperformance, the original managers are victims of their own success. They pivot to asset-gathering, as the steady stream of fees allows them to monetize their reputation long after their edge has decayed.

Summary

The nature of outperformance is zero-sum, exclusionary, and possibly isolating. Investing with outside managers who promise outperformance inherits the same issues of access and analysis. Instead of spending your time researching investments, you pay fees plus the time to find the managers, for an investment product whose slick pitch is likely selling noise as signal.

Learn More

- Alpha and the Paradox of Skill (Michael Mauboussin)

- Alpha and the .400 Hitter (CFA Institute)

- The Raw Materials for Active Management (Newfound Research)

- On Contrarianism (Moontower)

- More Evidence That Alpha Generation Is Shrinking (Evidence Investor)